The Myth of Moral Relativism

Searching for the mythical “Golden Age” of human morality

Photo by Nick Dunlap on Unsplash

(A seven-minute read.)

(Note: I’ve had this topic on the back-burner for a long time, but after coming across a tweet the other day, I’ve finally decided to put my pen to paper and bring these thoughts to light.)

I have a very simple question: when was it in human history that there was a “Golden Age” of collective morality?

I ask this question because there is a common thread that I hear and read within many Christian circles today which states that we live in an age of incredible debauchery and immorality—and there is one main culprit for such a reality: moral relativism.

What people mean by this, or at least I think they mean by this, is that they look at postmodernism, which they understand to promote the idea that there are no “moral absolutes,” that humans can do whatever feels right to them, and conclude that the world has sunk to such lows because everyone just does “what is right in their own eyes.” And if the world could just get back to believing in moral absolutes—that right and wrong objectively exist—then we could restore the collective morality that we’ve lost somewhere along the way.

A couple things, though: first, I’m not sure the idea of “moral relativism” is really a thing. I think people use terminology—like “my truth”—that seems to communicate such an idea; but, at the end of the day, most people do believe in some sort of higher, objective morality. It’s why we get zealous advocates for Black Lives Matter or #metoo. These are not moral relativists.

Secondly, and to my original point: when, exactly, prior to this alleged fall into moral relativism, was humanity’s collective morality any better?

Or even just limiting it to the “Christian” west: when were the peoples and lands that fell under the Christian banner collectively more holy and pure?

Was it in the fourth and fifth centuries, when Christians in the Roman Empire, finally enjoying the protection and favor of the state, took to violence to force conversions, burning down pagan temples and using the sword to compel religious adherence?

Was it in the eleventh century, when the Church initiated the Crusades, seeking to capture Jerusalem from Islamic rule, using all the tactics of warfare to achieve their ends?

Was it in the fifteenth century, as a part of the Church’s Inquisitions, as they sought to snuff out heresy—and burned people at the stake for refusing to convert?

Was in the sixteenth century when Protestant fought against Protestant—when, for example, Protestants in Zurich, via state sanction, drowned Felix Manz for affirming the belief in baptism by immersion? (He was not the last Anabaptist who was executed by his fellow Christians via this method.) Or was it when, in the same century, John Calvin participated in the execution of his theological opponent, Michael Servetus, for denying, among other things, the doctrine of the trinity?

Was it in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when Christians in Britain and America owned Black people like chattel, and justified this behavior by appealing to the “objective” truth of Scripture?

Was in the twentieth century, when Christians in America similarly denied Black people the right to eat at their diners and sit in the front of buses—and then mowed them down with fire hoses for simply demanding the right to vote? Or was it also, in the same century, when Black people in my own faith community were not allowed to eat in the cafeteria at the world headquarters—all because of the color of their skin?

Was it in February of 2022, when Vladimir Putin, who is a self-avowed Christian and who certainly doesn’t espouse “moral relativism,” invaded another sovereign state, threatening to use whatever means necessary—even nuclear war—to achieve his ends?

Was it during these times—before anyone apparently made any claims to “moral relativism”—that the world’s collective morality was so much better?

I ask again: when, exactly, was the “Golden Age” of collective morality?

I get it. There are many practices today—be they related to sexuality or gender or matters of life—that seem to be gross departures from biblical norms. I share many of those concerns and am equally troubled by various trends. Please believe me when I say this.

But I’m not sure that the way to prevent sliding into further societal immorality is by appealing to some mythical past or by insisting on some sort of “objective truth” that just so happens to align with our particular convictions and opinions. Such moves are simply seen as power-plays and eagerly resisted by the people we’re trying to reclaim from “moral relativism.”

Please don’t misunderstand me: while I unequivocally acknowledge my own limitations in fully grasping it, I do believe in absolute, objective truth!

I’m just not sure that the biggest reason for a low level of morality is because suddenly everyone became a postmodern and now believes in “moral relativism.”

Instead, I think to whatever degree society is collectively immoral, it’s because sin, selfishness, and pride lie deep within the bosom of every human being. And the selfish heart will always use whatever excuse it can, in whatever age, using what the philosophy of the day is, to justify its departures from the Jesus-way—be they the so-called objective truths of Scripture (as nineteenth-century Americans did when justifying slavery), or whatever the arguments of postmodernism might be.

People appealing to postmodernism are no more or less sinful than those who have appealed to Scripture to justify their own sins. Indeed, for every postmodern who may cite “my truth” to justify their sexual behaviors, for example, there were perhaps just as many moderns who appealed to “the truth” of the Bible to justify their brutal enslavement of Black people.

As missionary and churchmen Lesslie Newbigin put it: “Part of the reason for the rejection of dogma is that it has for so long been entangled with coercion, with political power, and so with the denial of freedom—freedom of thought and of conscience. When coercion of any kind is used in the interests of the Christian message, the message itself is corrupted.”

Yes, my insistence that others must change their behavior because of their obligation to “objective truth” is itself a form of coercion. In so doing, I am not appealing to a person’s good will but appealing to their sense of obligation, implicitly playing to their fear of what will happen if they violate the Powers of the universe.

So what’s the answer? Is it, to use a phrase that has probably been misattributed to Edmund Burke, for “good men to do nothing”?

I think, as I’ve touched on before, it’s a matter of conscientious people living winsome and attractive lives, sharing testimony rather than command.

The last thing the world needs is for religious people to act like we have a direct line to God and that we alone know exactly what absolute truth is (yes, I believe that the Bible does present absolute truth—but faulty interpretations in the past, like the Bible’s use to defend slavery, should give us a bit of humility when it comes to making sweeping statements about what we think other people should do based on the Bible).

Instead, let’s sweep our own side of the street. Let’s take the log out of our own eyes—following what we understand God to be telling us, rather than what we think he’s telling others. That’s a full-time job of its own. We live in a world where us religious people are more concerned about correcting others’ behavior than correcting our own. Imagine how different the world would be if we just all worried about ourselves?

So let’s live lives of empathy, humility, and grace.

That will go a lot further in nudging people away from behaviors we think are problematic than trying to exert our authority by appealing to some sort of “objective truth” that really comes across as gaslighting and a further attempt to control.

We can do all this without having to surrender our personal belief in the existence of moral absolutes. It’s just that by surrendering the need to insist on such ideas, we can shed the baggage of 1700 years or so of religious people who insisted on the certainty of their apprehension of “objective truth,” all the while committing such heinous acts in the name of their certainty.

In other words, when alleged “moral relativists” hear us say “we need to get back to objective truth,” what they often really hear is, “We need to get back to ideas that served as the basis for coercion, oppression, exclusion, and violence.”

And the sooner we can detach ourselves from such associations, the better.

As a Postscript, I wanted to share with you a little bit about my recent trip to Oxford for my doctoral studies. I returned on Friday after spending about a week there. It was, once again, a wonderful trip filled with many adventures. I got to listen to some awesome lectures and meet some wonderful people—in addition to catching up with new friends I’d made during my last trip.

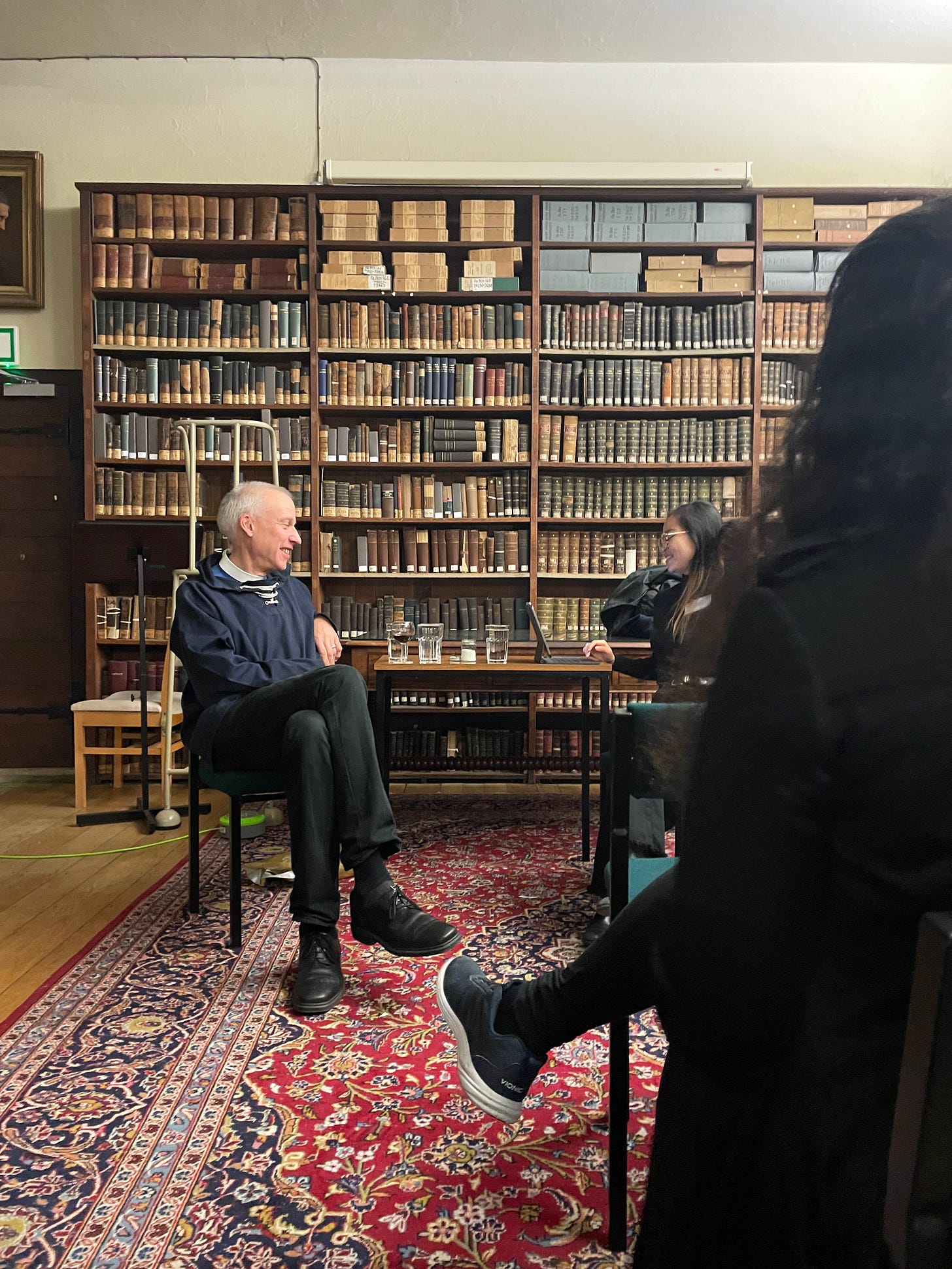

Among other things, I greatly enjoyed listening to Dr. Michael Lloyd last Monday night, during the Oxford Graduate Christian Forum’s weekly meeting (pictured below). Dr. Lloyd is the Principal of Wycliffe Hall, which is Oxford’s evangelical college. He spoke about the “problem of evil” during a very informal, “fire side” type chat. It was so thrilling to hear him articulate a perspective on this issue that sounded an awfully lot like what my particular faith community says on the subject—that evil’s existence in the world is not because God has ordained it, but because human beings have free will and because of the fall of “Lucifer” (as he’s been commonly referred to) and his demons, who’ve wreaked havoc on the universe.

He also spoke with great passion and pathos about how God’s character is revealed most clearly in Jesus—and how we understand, by looking at Jesus, that the God of Scripture is a God of love and humility. Again, he sounded just like a Seventh-day Adventist (or at least an Adventist who has his or her theology straight).

I was able to connect with him briefly after the meeting. He struck me as a very humble man, and I greatly appreciated both hearing and meeting him (as did my dad, who, along with my mother, was visiting with me at Oxford for a few days and joined me for the meeting).

I also sat in on a guest lecture by Dr. Bruce Hindmarsh, who teaches at Regent College in Vancouver, Canada, and is one of the foremost experts on the history of evangelicalism in North America. He spoke about how evangelicals read the Bible in the eighteenth century. It was really fascinating, with broad connection to my own area of research, and I was similarly excited to chat with him for a few minutes after the lecture.

On Thursday morning, I went to a seminar for graduate students who are studying church history (or as the Brits typically like to refer to it: “ecclesiastical history”). There were about ten of us sitting around tables in a small room, listening to Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch, who is an Emeritus professor of church history at Oxford, and one of the most well-known British church historians. He shared with us about his academic journey, as well as his own relationship to the Church of England, which has taken many twists and turns (not least of which because of his sexuality, which ultimately took him out of the Church).

Lastly, and perhaps most thrillingly, I went to a tiny sandwich shop on Thursday afternoon, which is one of my favorites in Oxford, and I looked over as I was standing in line, and there, right behind me, was Professor N. T. Wright. I had actually passed him on the street as I was walking to the shop, but it didn’t register until after he had passed. But I decided not to chase him down (as he was walking in the opposite direction).

So imagine my surprise when he ended up standing behind me in line (he must have turned around and come back, since he had been walking in the opposite direction). I introduced myself and for the next ten minutes or so, as we ordered our food and then waited for it, we had a wonderful chat.

For those who don’t know, N. T. Wright is arguably the world’s foremost scholar on the New Testament. He’s also someone who has been incredibly influential on my own thinking and theology over the last 15 years, through his writing and podcast, and seems to be a real humble man of God—which my ten minute conversation only confirmed. He was absolutely delightful to speak with and was greatly intrigued by my research.

Regrettably, we had only a few minutes to chat, but I’m hoping this chance meeting now opens the door for further connection on future trips to Oxford. Of course, I did the fan-boy thing and asked to take a picture with him—which he happily obliged.

I am still pinching myself that I get to study at (one of?) the world’s greatest university, and to meet and interact with such amazing people.

Shawn is a pastor in Maine, whose life, ministry, and writing focus on incarnational expressions of faith. The author of four books and a columnist for Adventist Review, he is also a DPhil student at the University of Oxford (what they call a PhD), focusing on nineteenth-century American Christianity. You can follow him on Instagram, and listen to his podcast Mission Lab.

I hear a lot of people who just want to get back to the way things were in the early church. EO and RCC argue about who is the original church which to them means most pure? Reformed folks look to the years of Luther/Calvin as the golden era. Agreed, it doesn't exist. We are to look forward to the return of Christ and the New Heavens/New Earth rather than looking back.