Finding My Epistemological Home

Going all-in on "critical realism"

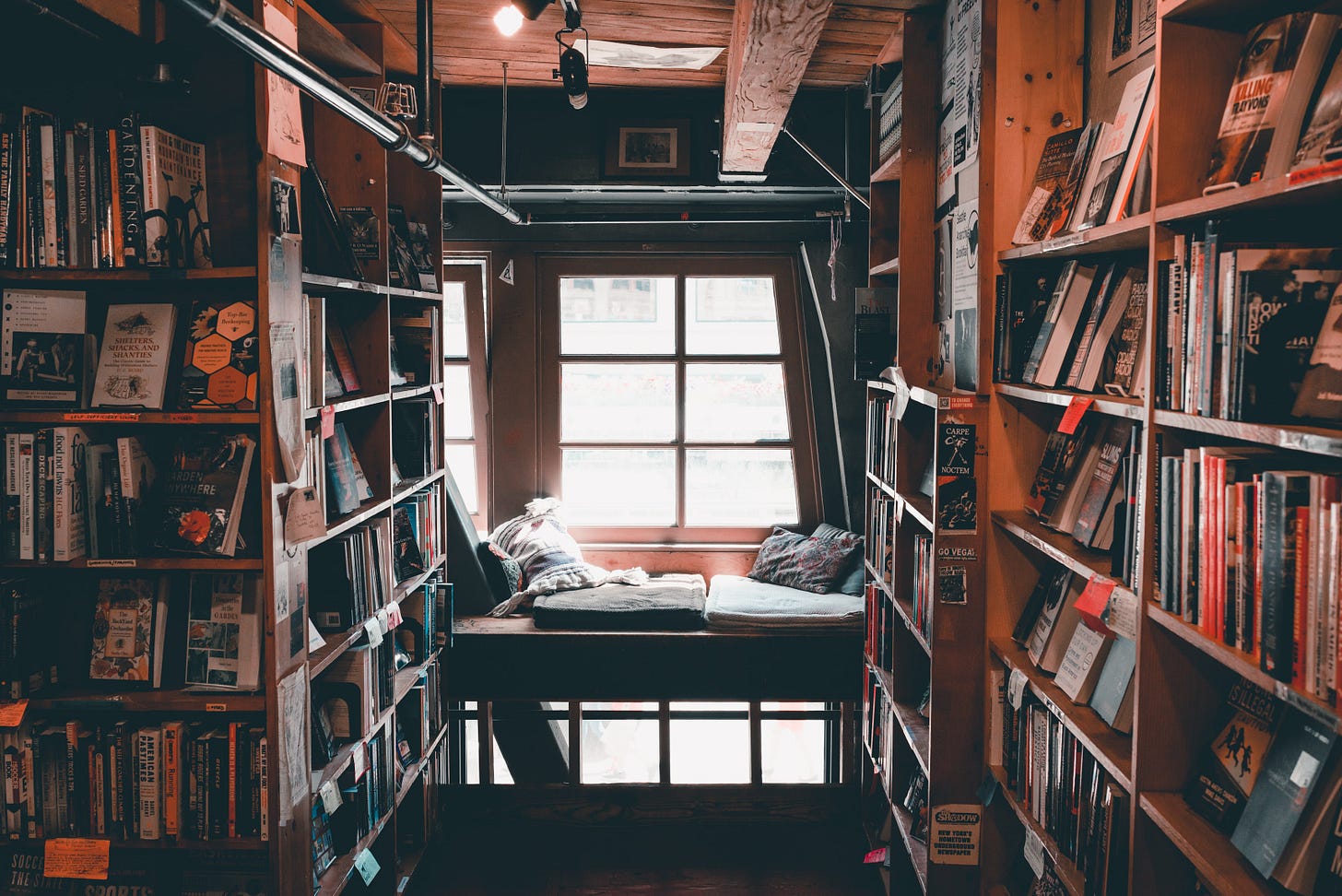

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash

(A word of warning: this post is really, really long - almost twice as long as a typical post. It is also very heady. So my apologies for that ahead of time. But I obviously think it’s a really important topic. If you want to skim it or just jump to the bottom line, make your way to the bottom of the post where in bold letters I say: “The bottom line.” That is where you can get the gist of this post without wading through all the technical jargon. Though, of course, I’d highly encourage you to give the whole thing a good read. And to read Part 2 - “Why Critical Realism?” - click here.)

Perhaps the most enlightening conversation I had while at Oxford a few weeks ago was one I had with my new friend, David M. Williams, who is a fellow DPhil student in Theology at Oxford. David is a great guy—an American who has been at Oxford for a few years, first doing his Masters and now his DPhil. He also serves the graduate community, essentially working as a chaplain of sorts for the equivalent of InterVarsity at Oxford.

As we ate Thai food at the Old Tom Pub, just across the street from Christ Church, we got to talking about the nature of knowledge and how we know what we know. And as I described for him my current wrestling on the topic—which I’ll further describe below—he suddenly stopped, looked up at me, and asked, “Are you familiar with critical realism?”

Over the next few minutes David unpacked this concept for me and I quickly became a disciple. Though I had heard about critical realism before—from another friend of mine also named David—it wasn’t until this David explained it to me that it finally sunk in and captivated my imagination. Since that conversation, about two weeks ago, I’ve been reading everything I can get my hands on about critical realism, feeling like I’ve finally found my epistemological home.

So let me explain it to you—with the important caveat that this post might be a little more heady, dry, and technical than other posts, and therefore not as interesting or relevant to some readers. But I would submit that it is such a hugely significant topic that has such far-reaching effects—so if you can hang in there with me for a bit, I think you will find it relevant and interesting.

But let’s start with a basic question: what in the world is epistemology?

Understanding epistemology

Epistemology is a fascinating and important topic. It’s basically the study of knowledge, dealing with how we make sense of the world. The Dictionary specifically defines it as “the theory of knowledge, especially with regard to its methods, validity, and scope. Epistemology is the investigation of what distinguishes justified belief from opinion.” In other words, epistemology is the study of how we make sense of the world, explaining the filters by which we determine what is true and what is not true.

For example, one school of thought within epistemology is empiricism. This is essentially the position that nothing can be believed—indeed, nothing is true—unless it is empirically proven using objective methods of observation. Thus, if someone was to come along and tell an empiricist that they’d just traveled from Australia all the way to the United States, walking all that way on water, the empiricist would immediately look suspiciously at such a claim because it would not align with their epistemology. The empiricists knows that people don’t walk on water, because it has never been empirically observed and reproduced, and so such a claim wouldn’t pass their epistemological filters.

We all have an implicit, and rarely an explicit, epistemology. We all have lenses through which we see the world. We all encounter claims or have experiences that either make sense because they harmonize with our epistemology, or sometimes don’t harmonize with our epistemology, in which case we either suspend judgment because we figure we will eventually find a way to harmonize it, based on further information, with our epistemology—or, in rare cases, we will be forced to find a new epistemology that makes more sense of the data (this is, in many ways, what we might call “conversion,” which is when a person has an encounter or experience that is so different from their previous understanding of the world that they come to embrace a new epistemology—a new way of looking at the world and making sense of it. N. T. Wright, who I will quote below in a different context, uses the term “narrative” to describe this. He says that we all live in stories—live in certain narratives—and conversion is essentially the process by which we start living into a different story.).

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, modern epistemology was birthed. This period is known as the “Enlightenment,” when humans in Western society became quite persuaded of their ability to know anything and everything. In some ways, they believed that omniscience was within their reach.

There are various schools of thought within this modern project—such as empiricism, positivism, rationalism—but in the United States, the philosophical framework that became most popular is known as Common Sense Philosophy, which had its origin in the Scottish Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. The Scottish philosophers utilized Francis Bacon’s scientific method and proposed that human beings, using the proper tools of observation and inductive reasoning, could arrive at and establish objective facts. Human beings could know, with 100% certainty, what the truth was. And since this knowledge was “common,” and thus available to anyone with a brain, if a person came to a different interpretation of the same data set, it meant either they were simply unintelligent or being purposely obstinate.

Simply put, eighteenth century, and especially nineteenth century, epistemology, particularly in America, insisted on human beings’ ability to know with absolute certainty that they’d arrived at the singular truth of a topic.

And this was, quite significantly, the prevailing epistemological framework of Protestants in America in the nineteenth century. Applied to the study of the Bible, every interpreter became fully persuaded that simply using the Baconian method—whether they realized they were using it or not—meant they could arrive at the singular meaning of a biblical text, resting with absolute certainty that they knew exactly what the text meant.

What’s more, having arrived at the place of certainty about the interpretation of the text, they eagerly concluded that anyone who interpreted the text differently was either being purposely duplicitous or allowing subjective factors to influence their interpretation of the text. But no one who applied the Baconian method, utilizing common sense, would arrive at a different conclusion, since a “plain reading” of the Bible would obviously yield the same interpretations.

It’s a long and complicated story, but by the end of the nineteenth century, many Protestants in America moved away from this epistemological approach to the Bible and Christianity. But not everyone.

Today, for the most part, evangelical Christians, including my own faith community, and especially those who are either implicitly or explicitly fundamentalist, still operate from this epistemological framework. Conservative Christians often speak with so much confidence about their religious convictions—as though they have direct access to the mind of God on every topic. The sort of “The Bible says it, I believe it, that settles it,” mantra, though it’s a bit of an extreme caricature, epitomizes this mentality.

What’s more, conservative Christians often operate from the belief that their interpretations of the Bible are absolutely true, and anyone who disagrees with them is absolutely wrong—since there is only one answer, and one can easily arrive at that answer by simply utilizing the proper Baconian tools of interpretation. Any hint of doubt about one’s interpretations of the Bible, or their community’s interpretations of the Bible, undermines their religious security, and is oftentimes the basis for exclusion from that community.

This may seem a bit extreme to some readers, but I’ve unfortunately found it to be often true. Theological and doctrinal certainty is deeply coveted by those who have embraced—whether realized or not—this Baconian Common Sense epistemology. Indeed, though rarely explicitly acknowledged, religious security is often based upon the degree to which a person is certain about their intellectual and doctrinal beliefs.

There are many people within conservative Christianity who have weighed such an epistemological approach and found it wanting (and thus “deconstructed” their faith as result). There are also many outside of Christianity in the West who have also found it wanting, and would have a hard time embracing evangelical Christianity because of its Baconian commitments (which begs the question as to whether we implicitly believe that a person must first be converted to modern/Baconian/Common Sense epistemology before they can embrace Christianity).

I have come to the point of affirming these concerns, greatly sympathetic to such pushback. After all, Christianity, especially in the last few hundred years, is littered with stories of over-confident Christians whose biblical interpretations turned out to be off base—sometimes with dire consequences.

Within my own faith community, as I’ve probably mentioned before, our forefather, William Miller, for all the great things he did, promoted a sort of Baconian method of biblical interpretation that, if followed, promised inerrant interpretation (he literally said that, if utilized, the interpreter “cannot be in error”). Using such a method, he convinced upwards of a half-million people that Jesus was returning in 1844.

For many, the only alternative to this modern Baconian epistemology is seemingly postmodern epistemology. This is a very cynical view of human knowledge that, at the very least, essentially proposes that our knowledge is completely conditioned by our context and therefore doesn’t reflect reality in any objective sense. We simply interpret the world entirely through our subjective experiences and there is no way to absolutely establish universal truth-claims that apply to all people at all times. In the more extreme forms of postmodernism, of course, there is no such thing as absolute truth at all.

For those who live by the modern Baconian epistemology, anything that challenges that framework feels like postmodernism. To even imply that our perception of reality might be significantly affected by our context and might be interpreted through the lenses of our experiences feels like the promotion of relativism or pluralism (for the Baconian, there are no lenses—and in fact the goal is to completely remove any lenses that might affect our ability to accurately interpret reality. That is, figuring out a way to observe something from the seat of complete objectivity is not only the goal, but entirely achievable within the Baconian framework.). And relativism, and the denial of absolute truth, is one of the major reasons why the world is seemingly spiraling into moral decay at breakneck speed—at least according to the Baconian.

For my own part, I freely admit that certain aspects of postmodernism have been attractive to me if the only other option is—what I perceive to be—the arrogance of modern Baconianism. To me, if the only two options are modernism and postmodernism, give me postmodernism (which is a scary idea to this Christian formed in Baconianism).

But then I learned about critical realism.

Introducing critical realism

So now, after 1776 words, I’ve finally come to the point of it all: critical realism. Not that critical realism is necessarily a conscious middle way between modernism and postmodernism, but it can be understood in that way.

Let me just rattle off some definitions and descriptions of critical realism by various theologians and philosophers, some of whom I know personally. My friend John Peckham, and professor of theology at my alma mater, Andrews University, succinctly explains critical realism thusly: critical realism says

that there is a real world independent of one’s beliefs, about which one can have true knowledge, alongside the crucial recognition that human knowledge is fallible, theory-laden, and historically and culturally conditioned. Therefore, we can know but we know only in part (cf. 1 Cor 13:9-12) and thus should maintain humility regarding the extent and accuracy of our knowledge, without retreating from rigorous application of our God-given faculties toward knowing Him and our world as accurately as possible (Canonical Theology: The Biblical Canon, Sola Scriptura, and Theological Method, p. 138, n. 115).

For his part, John subscribes to a “minimal conception” of critical realism—meaning, as he explained to me in an email, he believes it in broad strokes without committing to all the various nuances and explanations of it that various philosophers might propose.

Similarly, David K. Naugle, in his 2002 book, Worldview: The History of a Concept, explains critical realism this way:

It posits an objectively existing world and the possibility of trustworthy knowledge of it, but also recognizes the prejudice that inevitably accompanies human knowledge and demands an ongoing critical conversation about the essentials of one’s outlook. This viewpoint may also be summarized in four basic propositions: (1) an objective, independent reality exists; (2) the character of this reality is fixed and independent of any observer; (3) human knowers have trustworthy cognitive capacities by which to apprehend this fixed reality, but the influence of personal prejudices and worldview traditions conditions or relativizes the knowing process; and (4) truth and knowledge about the world, therefore, are partially discovered and certain and partially invented and relative (p. 324).

Naugle goes on to explain that critical realism is

a blend of objectivism and subjectivism, acknowledging both a real world and yet real human beings in all their particularities attempting to know it. It places neither too much nor too little confidence in human reason, but recognizes what human cognitive powers can and cannot do. This position avoids the arrogance of modernity and the despair of postmodernity, but instead enjoys a rather modest, chastened view of knowledge marked by humility. . . . The consequence of critical realism is neither dogmatism nor skepticism, and its mood is neither excessively optimistic nor cynical. . . There is the persistent need, therefore, for interaction with others and other perspectives to challenge or certify an individual’s knowledge of the nature of things (pp. 324-325).

Lastly, way back in 1992, N. T. Wright—my fellow Oxford man—was pivotal in introducing the idea of critical realism to evangelicals in his book The New Testament and the People of God. Explaining that there is “no such thing as a god’s eye view” that is “available to human beings,” Wright explained that critical realism

is a way of describing the process of “knowing” that acknowledges the reality of the thing known, as something other than the knower (hence “realism”), while also fully acknowledging that the only access we have to this reality lies along the spiraling path of appropriate dialogue or conversation between the knower and the thing known (hence “critical”). This path leads to critical reflection on the products of our enquiry into “reality”, so that our assertions about “reality” acknowledge their own provisionality. Knowledge, in other words, although in principle concerning realities independent of the knower, is never itself independent of the knower (p. 36).

After pointing out how human beings, when processing information, all bring various subjective realities to the processing of that information—whether influenced by their experiences, the community to which they belong, and so forth—Wright concludes by insisting that “any ‘realism’ which is to survive has to take fully on board the provisionality of all its statements” (Ibid.).

So after navigating through all those lengthy quotes, let me try to succinctly explain what critical realism is if you had a hard time getting through the fog. In essence, critical realism proposes that objective reality truly does exist outside our perceptions of it, but that our ability to fully grasp that reality is limited and influenced by our finite and fallible perceptions of that reality. In other words: we can make statements that accurately describe reality, but we must always be humble about those statements, since we don’t see the full picture and our perception is inevitably conditioned by our circumstances, experiences, and location.

The bottom line: unlike postmodernism, critical realism proposes that objective reality exists; but, unlike modernism, critical realism encourages humility regarding our claims about that objective reality.

If you made it through this whole post, congratulations! I hope you found it helpful. Next week, I will pick this theme up for Part 2 and explain why it is I believe it’s critically important that we embrace critical realism.

(To read Part 2 - “Why Critical Realism?” - click here.)

One more thing from my trip to Oxford! As you may or may not know, I’m a bit of a hobby photographer, videographer, and drone pilot. Though the flying was a bit challenging, due to strong winds (and lots of rain), I was able to get my drone up into the skies a couple days while in Oxford. The results are below. I hope you’ll enjoy!

Shawn is a pastor in Maine, whose life, ministry, and writing focus on incarnational expressions of faith. The author of four books and a columnist for Adventist Review, he is also a DPhil student at the University of Oxford (what they call a PhD), focusing on nineteenth-century American Christianity. You can follow him on Instagram and Twitter, and listen to his podcast Mission Lab.

I’m going to try loading this post in Speach Central. I have been looking for a exactly this information. It would be great if you would do some seminars on social media. I would definitely be there. Or do some YouTube videos. I am excited to hear what you are learning. God bless, Jeanne.