Should Christians Be "Woke"?

Wading into tenuous societal waters

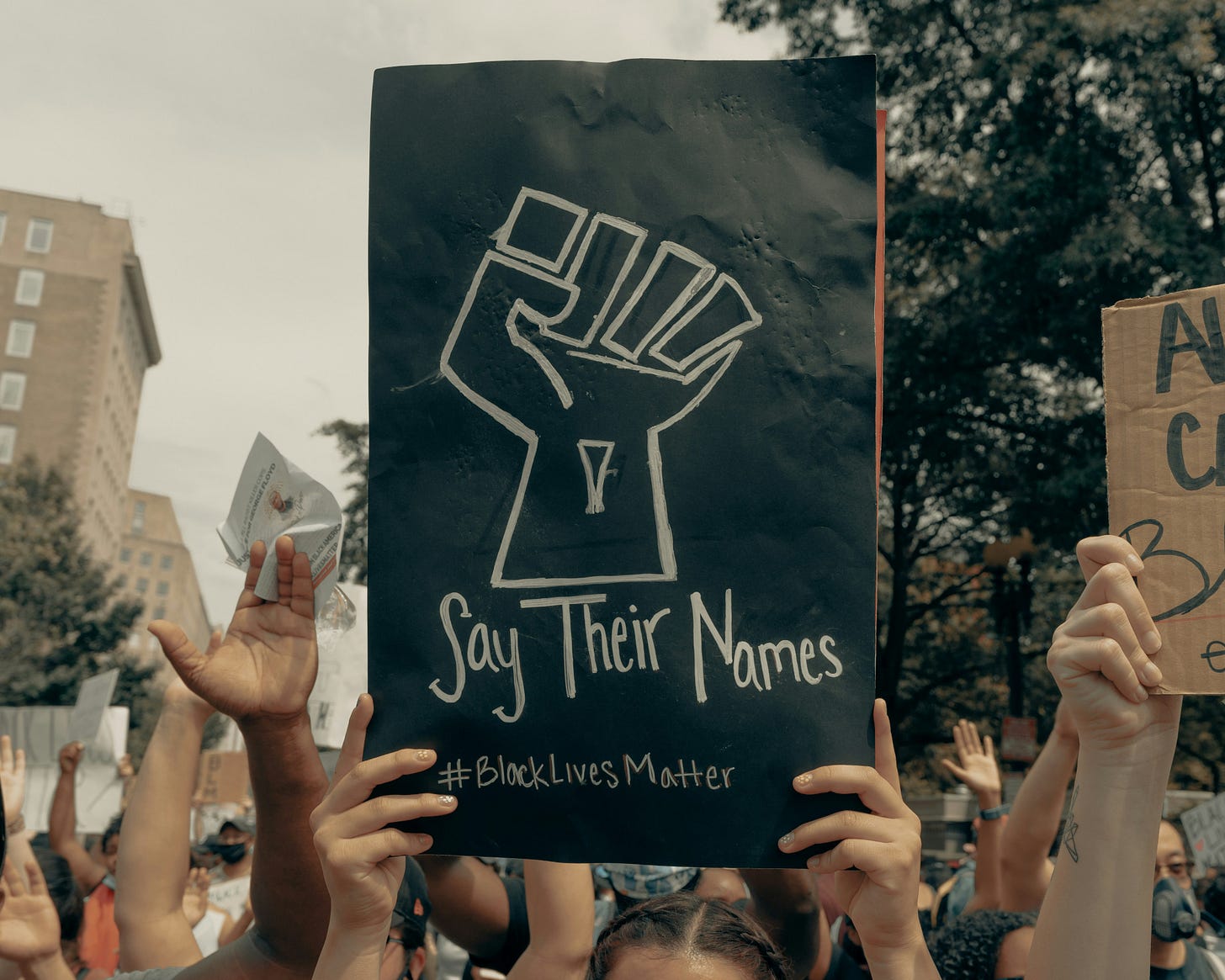

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash

(An eleven-minute read.)

(Note: this is one of my longer pieces—though it’s actually edited down quite a bit from what I originally wrote. That’s because I think the topic—which is a very important one—deserves a lot of careful and nuanced discussion, especially as we acknowledge and celebrate Black History Month in February. So thinks for giving it an honest and thoughtful read.)

A few days ago, someone forwarded an article along to me which proclaimed that the “Harvard of Christian schools” had gone “woke.” The school in question is Wheaton College—perhaps the most prestigious evangelical college in the world and the alma mater of people like Billy Graham, Rob Bell, and John Piper.

According to the article, Wheaton has become increasingly “woke” over the years, promoting “Marxism, religious syncretism and segregation,” and, of course, critical race theory.

It’s not my interest in this piece to discuss whether or not Wheaton College—or any other Christian college—is or isn’t becoming “woke” (you can read Wheaton’s response here).

What I want to discuss—perhaps foolishly—is the underlying assumption that, granting the claim that Wheaton has become “woke,” this is a bad thing and a move away from biblical Christianity.

Simply put, I want to wrestle with whether Christians should or shouldn’t be “woke.”

What is “woke”?

Of course, I know I’m stepping into a hornets’ nest! Fewer topics elicit more controversy these days than questions about race, gender, and sexuality. It sometimes feels like these matters are purposely highlighted as a means of being intentionally divisive.

I thus don’t write to be divisive or controversial. I have no interest in jumping on any bandwagon or trying to score political or religious points.

I do believe, however, that people of faith should not only be informed of but have convictions about issues that affect society more broadly. While I’m of the belief that God’s kingdom is ultimately “not of this world,” we are to work out the ethics of God’s relational love in this life—insofar as it neither minimizes the life to come nor contradicts our commitment to the gospel.

And what do the “ethics of God’s relational love” look like?

Do those ethics harmonize with or contradict being “woke”?

One of the biggest challenges, of course, is that most people seemingly aren’t working from the same definition. What does it even mean to be “woke”?

For some—especially those who are “anti-woke”—the label seems to be applied to any “progressive” idea that one either disagrees with or doesn’t understand. It’s sort of a “catch-all” word that has more “rhetorical power” than definitional clarity, purposely employed by critics to elicit a visceral reaction.

Using the word in this way, though, according to Princeton-trained sociologist (and evangelical) Jessamin Birdsall, is “intellectually lazy.” We should instead learn to express “our disagreements or discomforts in more concrete terms,” she proposes, as this “will be more fruitful than simply dismissing a person or an organization as ‘woke.’”

Admittedly, one of the reasons for the ambiguity is because the word has gone through a bit of an evolution. Birdsall herself identifies three stages in the term’s evolution, beginning with its first usage in the early-twentieth century within the African American community.

Starting in the 1940s, she explains, the term was used as “an admonition to stay awake and alert to racial injustice.” As such, people were to remain “conscious of how racism operates in order to protect oneself and to protect and advocate for others.”

Thus, to be “woke” during this time was to be aware of and alert to racial inequities and injustices.

Birdsall then explains that the idea of “wokeness” began to expand during its second stage in the late 2010s, when it started to speak not only of racial injustice, but other issues such as climate change and transgender rights. The term thus indicated a “commitment to see and understand perceived injustices of all kinds.”

Finally, in the third stage, which we presently find ourselves in, the term is seemingly employed more by its enemies than its advocates. Though some people still use it positively, the vast majority use the term in a “pejorative” sense, employing it to quickly and easily dismiss people and the ideas they espouse.

I’m therefore unsure how helpful it is to continue to use the phrase itself. I certainly don’t think critics should use it in a pejorative way—though advocates may still find that the term can be redeemed.

To this end, I appreciate how philosopher J. Spencer Atkins has both defined and advocated for the term and the posture. Writing in the philosophical journal Social Epistemology last year, Atkins introduced what he called the “group partiality view,” where to be “woke” means one is “partial to the needs and interests of marginalized and oppressed groups.”

They thus have a bias towards people of such groups—just as one has a bias towards one’s friends more than non-friends—and implicitly give such people the “benefit of the doubt.”

This doesn’t mean that being “woke” means one is being irrational and/or ignoring or denying the real “facts” of a given situation or claim. It simply means that there’s a higher “burden of proof” that’s required in order to convince the “woke” person that their perspective is false or that their “friends” are wrong (just as you’d require a higher burden of proof if a person brought a charge against someone you knew and trusted than if they brought it against someone you didn’t know or trust).

If we therefore take Atkins’s model of being “woke” as a minimal definition—being aware of injustice and partial towards those who are the recipients of this injustice—we’re prepared to alas answer the question: should Christians be “woke”?

But as a way of answering this question, I think we need to ask two further questions: first, what do (or did) the authoritative Christian voices say about our treatment of and attitude towards oppressed and marginalized groups?

And secondly, do oppressed and marginalized groups even exist today?

“Thus saith the Lord”

By “authoritative Christian voices” I primarily mean Scripture. Though I certainly have my concerns about the way we use the Bible, and don’t believe we should practice a naïve biblicism, I still consult Scripture as my primary—though not only—source of religious knowledge and practice (as I’m sure many Christians do).

In this case, and at the risk of resorting to a sort of “proof-texting” approach where we just string together a bunch of disconnected and out-of-context verses, the biblical witness seems pretty clear to me: God has a jealous—and perhaps even angry—regard for the downtrodden and oppressed. He zealously advocates for and seeks to protect widows, orphans, and foreigners—and much of the critique of his people stems from their tendency to exploit such groups, failing to treat them with justice and compassion.

I could multiply the biblical passages, but let me cite just a few. From the prophet Isaiah, we read:

“Woe to those who make unjust laws, to those who issue oppressive decrees, to deprive the poor of their rights and withhold justice from the oppressed of my people, making widows their prey, and robbing the fatherless” (Isaiah 10:1-2, NIV).

From the prophet Ezekiel, explaining why God’s people had gone into Babylonian captivity, we read:

“The people of the land practice extortion and commit robbery; they oppress the poor and needy and mistreat the foreigner, denying them justice. . . . So I will pour out my wrath on them and consume them with my fiery anger, bringing down on their own heads all they have done, declares the Sovereign Lord” (Ezekiel 22:29, 31, NIV).

Simply put, God really, really, really cared about how marginalized people were treated.

Even the heart of the fourth commandment, which my particular faith community obviously makes a big deal about, has this commitment to justice embedded in the practice of the Sabbath.

After all, in entering into weekly rest, Israel was to extend this same rest to their “manservant” and “maidservant,” and “the stranger” who was within their “gates” (as well as cattle, by the way!). The “stranger” was a traveler or alien—someone who wasn’t native-born and thus didn’t naturally possess the same rights and protections of a citizen.

In other words, while the people of Israel were to enjoy the benefits of resting from their labors on the Sabbath, they weren’t to take advantage of their servants or the “stranger,” and require them to do the work the people of Israel were resting from.

Though God made it clear, just a few chapters later, that they were never to “oppress a stranger” (Exodus 23:9), the Sabbath was especially a weekly reminder of the equity and justice that was to be extended to and enjoyed by all.

For the sake of time, I won’t go through the litany of New Testament passages—but suffice it to say, I don’t think God suddenly changed his mind and decided that all that really mattered after Jesus came was whether people were “saved” or not. He was still jealously concerned about matters of societal and relational justice.

Indeed, through the life of Jesus, and the testimony of his apostles, we repeatedly encounter God’s heart for the marginalized and oppressed, to the point where James—the brother of Jesus—said that “pure and undefiled religion” was expressed through “looking after orphans and widows in their distress,” and not showing “partiality” to the rich and powerful (see James 1-2).

From cover to cover, Scripture seems pretty conclusive to me.And I think most people who give the Bible an honest reading would come to a similar conclusion.

The biblical writers seemed quite aware that there were groups of people—orphans, widows, strangers, foreigners, even sexual minorities (i.e., eunuchs)—who were not in positions of power and didn’t have access to influence and advantage.

And, tragically, these groups of people were frequently taken advantage of, exploited, and oppressed by other groups of people who were in positions of power.

And this made God angry.

“Yeah, but . . . ”

I think if one is able to at least see this reality in Scripture, it’s a huge step.

And yet there are many who, no doubt, are either hesitant to admit the pervasiveness of this theme in Scripture, or who are incredibly reticent to connect it with anything going on in the present.

I get it. Those who seem to beat the “woke” drum the loudest seem to have little commitment to the Bible—with many perhaps trying to detach society from any religious moorings altogether.

At the same time, we live in an age—at least in America and other Western countries—where egalitarianism is the law. Equality is written into our most important documents, and discrimination on the basis of race, gender, or sexuality has long been illegal.

We’ve even seen stuff like “Affirmative action” and intersectionality, where racial and sexual minorities have been given special treatment and advantages.

This is obviously a huge subject, and one that requires its own extended and nuanced treatment.

But I just want to note one possible response that gives me pause.

J. Spencer Atkins, the philosopher noted above, talks about the “moral stakes” that are implicitly involved with any particular belief or action. As he notes, “beliefs with high stakes are harder to justify than beliefs with lower stakes. Our beliefs often have outcomes that define the stakes of the belief.”

Beliefs with higher stakes therefore require a greater burden of proof than ones with lower stakes.

For example, if you need to catch a train for a job interview and you believe the train leaves at 9am, you’ll devote a lot more time justifying the belief that it leaves at 9am than if you simply need to catch the train because you’re going shopping. Missing the train for a job interview is a much bigger deal than missing it to go shopping—so the time spent confirming the belief will be in proportion to the stakes.

This is just one way I relate to the question of whether there are oppressed and marginalized groups today that need my attention and advocacy. I can argue about statistics; I can argue with people’s perceptions of the way they’re treated. But in some ways, both these things can be twisted and misinterpreted.

Instead, I can just ask the question: what’s at stake?

It seems to me that, in a sort of “Pascal’s Wager” kind of way, there’s a lot more to lose if I deny there are oppressed and marginalized groups today than if I affirm it. To some degree, lives are literally at stake.

Simply put, if I believe there are marginalized groups today and there really aren’t, what have I lost? Not much—except for probably a bit of power (which, I’m guessing, a lot of people are afraid of losing).

But if I believe there aren’t marginalized groups today and there really are, it has much more dire consequences.

I know this is perhaps a very simplistic way of looking at the question, and a lot more could be said. But it’s just one reason why it makes sense to me to have a bias towards those who claim they experience marginalization and oppression.

So bottom line: should Christians be “woke” or not?

I’ve covered a lot of ground here—and yet I’ve merely scratched the surface.

But what’s the bottom line? Should Christians be “woke” or not?

I’m not sure if labels are or aren’t helpful, but it’s my genuine conviction that Scripture demands that I remain vigilant when it comes to my awareness of and advocacy for groups of people who are marginalized, oppressed, and mistreated.

And I do believe that such groups of people exist today (it would be a very strange and rather exceptional phenomenon in the history of our sinful world if there weren’t any marginalized and oppressed groups of people).

How that all gets “cashed out” is a topic for another day (though suffice it to say here: I don’t believe everything that gets pushed as “woke” is something I must get on board with—nor that I must be consumed by it as a “political” issue).

But, at the very least, I’m of the conviction that as a follower of a Man who had a jealous regard for the disadvantaged and the “least of these,” and as someone who believes God’s ultimate purpose is to bring the universe back to a place of full safety and security, my default posture is to look for ways to lift up the downtrodden and disheartened, rather than deny and delegitimize their pain.

Shawn is a pastor in Maine, whose life, ministry, and writing focus on incarnational expressions of faith. The author of four books and a columnist for Adventist Review, he is also a DPhil (PhD) candidate at the University of Oxford, focusing on nineteenth-century American Christianity. You can follow him on Instagram, and listen to his podcast Mission Lab.

Thanks for your thoughtful post on this Shawn! I especially think the idea of using such broadly defined labels (eg, "woke" and others), especially to label those we disagree with, as being "intellectually lazy".

So….. yes? (Love your woke Australian friend 😝)