(An eight-minute read.)

In the opening pages of the first chapter of Love Wins, which is entitled, “What About the Flat Tire?” Rob Bell recounts a time his church hosted an art show that focused on peacemaking, inviting a number of artists to share work that communicated their understanding of what it meant to be a peacemaker. Included in one woman’s offering was a quote from Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian dissident who utilized nonviolent resistance to help liberate India from British rule.

Many people found the quote to be quite inspiring, but not all. Apparently, someone attached a piece of paper to the woman’s work with these simple words: “Reality check: He’s in hell.”

In his typically ironic way, Bell responds in the book with incredulity. “Really?” he wonders. “Gandhi’s in hell? He is? We have confirmation of this? Somebody knows this? Without a doubt?”

He then spends the next few pages taking potshots at various versions of Christian salvation that are fraught with inconsistencies. Much of it is low-hanging fruit, but it’s classic Rob Bell, full of far more questions than answers, and it’s mostly spot-on.

Perhaps my favorite part is when he tackles the issue of whether people’s salvation is dependent on other people telling them about Jesus. “If our salvation, our future, our destiny is dependent on others bringing the message to us, teaching us, showing us,” he wonders, “what happens if they don’t do their part?” And then he asks this question, pregnant with ironic beauty: “What if the missionary gets a flat tire?”

Perhaps it’s not surprising, but the book, published in 2011, got Bell kicked out of the evangelical club. A few years before evangelicals started complaining about “cancel culture,” they canceled Rob Bell. In their minds, he undermined the traditional view of the existence of a never-ending, ever-burning hell, and he ultimately promoted universalism, maintaining that everyone, in the end, would be saved.

It was an interesting episode in the life of American Christianity, with mega-famous Reformed pastor John Piper famously—and perhaps gleefully—tweeting out, “Farewell Rob Bell,” seemingly reflecting an eagerness within certain circles of evangelicalism to tightly police the bounds of biblical doctrine.

Bell hasn’t been the same since, transitioning from being one of evangelical’s most famous and influential stars (Time magazine had, around the time of the kerfuffle, named him one of the 100 Most Influential People in the World), to essentially becoming persona non grata within conservative American Christianity.

I can’t speak with any authority as to whether Bell was or wasn’t denying the existence of an ever-burning hell or whether he was pushing the idea that everyone, in the end, would be saved (his subsequent theology would lead one to believe that he was guilty as charged—though, as I’ve written recently about similar situations, his critics may have “willed” those views into existence for him).

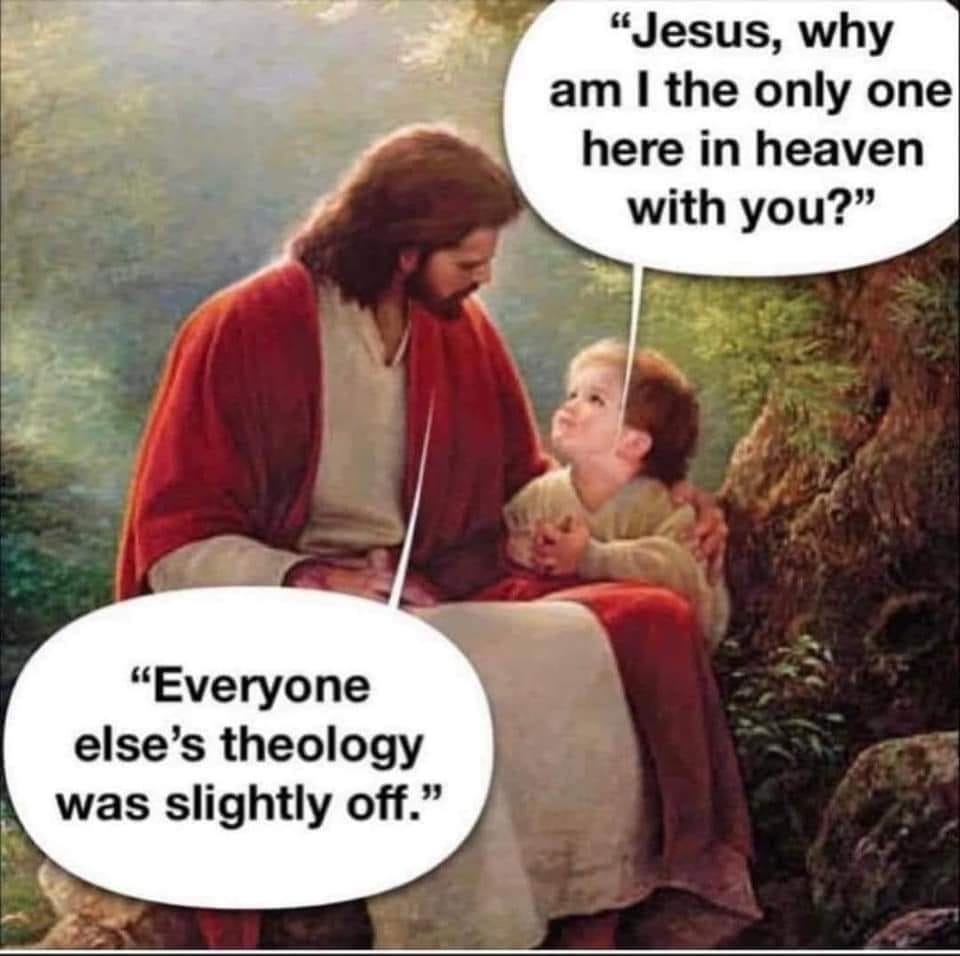

But I revisit this episode, a decade later, because I thought of Bell’s questions in the opening pages of the book when I saw a meme the other day—featured above—that was equally pregnant with ironic beauty and meaning.

There is so much packed into this little meme, but it really boils down to the question of how much a person has to know, or how right their theology has to be, in order to ultimately be saved.

Will God keep people out of heaven over theological technicalities? Will he let in only those who say the right prayer or affirm the right doctrinal formula?

Will only Christians be in heaven?

I want to wrestle with these questions a little bit—though after a few brief but important caveats.

Two Caveats

The first caveat I want to mention is that “getting into heaven” or “being saved” is not, I don’t believe, ultimately the most important issue at stake in the whole Jesus-story. Many Christians view this as the end-all-be-all of the whole project, however—as though “being saved” is all that matters.

I believe the story has a bigger goal in mind, though. I believe that bigger goal is the restoration of the world—and actually, the whole universe—to complete safety, peace, and love. And thus, as a part of that story, God is seeking to restore his image in humankind.

Nevertheless, I think there will be a definite point in time when, as a part of the story, there will be people who are given the gift of immortality, never to die again (or for the first time). Even though I don’t think this is the whole point of the story, it is still a part of it and in this post I am wrestling with the question of what separates those who end up living forever and those who don’t (and yes, I do assume that there will be some who don’t end up living forever).

The second caveat is that, while you may detect a subtle air of condescension from me towards those who think “living forever” is dependent on theological precision, I must mention that I also get it. I am a Protestant. I believe Protestants rightly pushed back against Catholic teaching which essentially said that performing the right rituals is what earned God’s love and the right to live forever.

When Martin Luther was on his knees, climbing Pilate’s stairs in Rome and beating himself up over his sins, and Paul’s quoting of the prophet Habakkuk that “the just shall live by faith” came to mind, that was an important turning point in religious and human history. It brought great relief and moved Christians’ security away from behaving the right way to believing in the right Person.

As a Protestant, I fully embrace the foundational—and, I’d say, biblical—teachings of Protestantism: Scripture alone, Christ alone, faith alone, grace alone, and glory to God alone. And I understand why (some) Protestants thus make such a huge deal about right teaching and right belief.

But I think these need to be explained and nuanced. Because, at the end of the day, I don’t subscribe to the idea that those who simply believe and give mental assent to the right doctrinal information are the ones who will be “saved.” I believe “faith” has broader meaning and application.

And now, in (hopefully) less than 500 words, I will try to explain.

Who Will Be Saved?

The Apostle John, in his first letter, shares an interesting thought. The whole book makes much of love (the word is used in this small book more than any other book of the Bible), and one verse in particular catches my eye relating to our present question. “Beloved, let us love one another,” John encourages for the umpteenth time. “For love is of God.” And then he drops this provocative idea: “Everyone who loves is born of God and knows God.”

Did you catch that? He says that everyone who loves is “born of God” and “knows” him. Everyone. No qualifications.

We might put it this way: any person who embraces a life of other-centered, self-denying love has been, to use familiar language, “born again.” Indeed, they “know God.”

And I’d add this: they know God whether or not they know they know God.

How can I say this?

Because such an idea is sprinkled throughout the teachings of Jesus.

It seems that in just about every story where Jesus explains who the people are that are living according to the principles of his kingdom, the emphasis is on, as Lesslie Newbigin puts it, “surprise.” Those who think they’re in are actually out and those who think they’re out are actually in.

I could cite example after example, but perhaps the most thought-provoking is the story Jesus tells of the sheep and the goats in Matthew 25—which illustrates the great judgment where God declares his decision about who lives forever and who doesn’t. According to the parable, the judgment comes down to whether people did or didn’t feed, clothe, and care for the poor and needy. Those who live forever did these things, and those who don’t didn’t.

But the great shock is that, according to Jesus, in feeding and caring for the poor, the “saved” actually did those things for Jesus. “Inasmuch as you’ve done it for the least of these, you’ve done it to me,” Jesus said (Matthew 25:40). In other words, the “saved” had encountered, cared for, and served Jesus without even realizing it.

This echoes what Matthew had recorded a number of chapters before where Jesus had similarly said that it’s not those who say “‘Lord, Lord,’ [who] will enter into the Kingdom of Heaven; but he who does the will of my Father” (Matthew 7:21). Here, Jesus makes it clear that it’s not those who say the right things or who believe the right things that will be saved, but simply those who choose to live out the principles of his Father’s love.

I could go on, but I trust you understand the point.

This is not a “salvation-by-works” scheme. We don’t earn God’s love by what we do.

It’s simply to say that, at least as I understand the Bible, those who end up living forever will be those who, to whatever degree they have encountered God’s love (whether or not it’s ever been explicitly articulated to them or attributed to the God of Scripture), have had their hearts moved by that love and are choosing to grow in their appreciation and living of that love.

In other words, whether I’m Christian or non-Christian, Buddhist, Muslim, Jewish, atheist, or whatever else, the question comes down to this: have I embraced love?

To be clear, I don’t have to be perfect in my embracing and living out of that love, but I believe those who are a part of God’s kingdom are demonstrating that the trajectory of their lives is ever-growing and expanding in the expression of love. And this is what it means to “live by faith.”

This raises all sorts of other questions, of course—from what the purpose of “evangelism” is, to what role, if any, “right” theology plays—but those are questions for other days and other posts!

Until then, the bottom line for me is, no, it won’t only be Christians who are in heaven. It will be those who, from whatever religion or non-religion, have embraced God’s love and who are living by that love (thus demonstrating that they would be at home in an eternity where only love is operative).

And some of those may even be Christians.

A few of today’s paragraphs were lifted from my newest book, The Table I Long For: Learning to Participate in the Mission and Family of God, where I spend a few more pages reflecting on this issue, as well as detailing my missional journey over the last few years.

I’ve been waiting until the book is fully available on Amazon in order to promote it more openly (and annoyingly). But until then, you can order a physical copy here if you’re in North America (or here if you’re in Australia, or here if you’re anywhere else), or order the Kindle version from Amazon here.

Shawn is a pastor in Maine, whose life, ministry, and writing focus on incarnational expressions of faith. The author of four books and a columnist for Adventist Review, he is also a DPhil student at the University of Oxford (what they call a PhD), focusing on nineteenth-century American Christianity. You can follow him on Instagram and Twitter, and listen to his podcast Mission Lab.

What about a Movie Universe which is about people from planet earth?

Everyone speaks english in that movie…

Not only the christian people but also asian people, people from africa and even mexican people and itallian people and the french ones, too…

They probably want to go to heaven and no, not all of them are christian and should not have to be christian for that.

+++++++

Anyway, could you help us against James and Jacob please? Their names are connected to ideas such as treachery, sheeming, assassination and stealing thrones…

If the missionary got a flat tire, then maybe the 'call' got sent to and picked up by 'a neighbor' who 'ministered' to whomever the 'missionary was on the way to 'minister' to. Can anybody be a missionary? Out here with wondering thoughts. Thank you sharing this post.