Photo by Magda Ehlers: https://www.pexels.com/photo/cutouts-of-letters-4116661/

(Note: try as I might, I couldn’t keep this piece under 1500 words [and I’d prefer even under 1200 words]. But I wanted to wrap up this mini-series in this piece, rather than have a Part 3. So I hope you’ll stick with it. I think it’s such a hugely important topic, and I had a lot more to say, but left much of it unsaid.

To read Part 1, click here.)

(A ten-minute read.)

Imagine two scenarios.

Scenario one: your next-door neighbor has just tragically lost her husband. You’re talking with her, and in great anguish and pain, she cries, “I’m so thankful he’s watching me right now from heaven. That gives me so much comfort.”

In response, you say to her, “Well, actually, the Bible doesn’t teach that. The Bible says that the dead don’t know anything.”

Question: have you shared the truth with your neighbor?

For those reading who may not be from my faith community, you may be confused by the scenario. But let’s just say, for the sake of argument, that a person doesn’t immediately go to heaven after death, but experiences some sort of unconscious “sleep,” awaiting the resurrection when Jesus comes back.

So I return to my initial question: have you shared the truth with your neighbor?

Some would probably say that you have shared the truth, but your timing is off.

For me, I would put it this way: you may have shared factually correct information, but you’ve not actually shared the truth.

Scenario two: a Christian pastor, who’s having an affair with multiple women, preaches a sermon on the “sanctity of marriage” and how it’s between one man and one woman and not between two men or two women.

Question: has he shared the truth about marriage?

Some would probably say he’s shared the truth about marriage but he’s a hypocrite.

But I’m not so sure.

Because, contrary to what us modern thinkers—the heirs of Platonism and the Enlightenment such that we are—have come to believe, “truth” is not a synonym for factually correct information.

Truth, from a biblical perspective, is so much more than that.

Why is this so important?

Last week, I discussed the idea of “truth” and noted that the biblical understanding of truth is different than the version that Greek philosophy and the Enlightenment have given us.

Put simply, for thinkers like Plato and Descartes, “truth” means correct abstract information—something that can be proven with propositions, no matter the time, place, or context. It lives in the abstract rather than in the concrete realities of relationships, context, and lived experience.

The writers of Scripture had a different understanding of truth, however. “Truth” didn’t equal correct abstract information. Truth meant reliability and dependability. It was that which one could count on.

It was therefore intimately connected to embodiment and context. It was personal.

This doesn’t mean that the biblical writers didn’t make factual claims or arguments. They made many, of course.

But those factual claims were as much accepted on the basis of the credibility of the one making the claim, and determined to be true to the degree that they could be trusted and relied upon.

Thus, for example, when the apostles said that “Jesus has risen from the dead,” their lives of love provided credibility for the claim, and the claim itself was seen as leading to consistent and reliable fruit.

It’s no wonder, then, that when Jesus defined “truth,” he didn’t offer a syllogism.

Instead, he offered something radically different.

He said, “I am . . . the truth” (John 14:6)

Truth, for Jesus, wasn’t a proposition; it was a person (himself).

Therefore, when Jesus sought to bring “truth” to people, he didn’t simply bring ideas and propositions. He brought himself.

So why is this idea so important to me?

Let me try to “cash” this out (even as I admit that I’m still sorting through how it all works).

For me, this is one of the most important concepts we can wrestle with because it has huge implications for at least three areas of life in general and spirituality specifically.

Those three areas have to do with ethics, epistemology, and evangelism.

Let me unpack them.

Ethics

When we believe that “truth” equals factual correctness, we often end up prioritizing factual correctness over ethical goodness.

Put another way, too many people—especially Christians—care more about being propositionally right than ethically just.

The fruit of this attitude—whether people embrace it explicitly or implicitly—has been extremely rotten. So often, we’d rather be correct than kind.

This is partly why, I’d submit, that the “postmodern” age (to whatever degree we’re still truly living in a postmodern age) has been skeptical of capital-T Truth claims. Modernism gave us both “objective” truth as well as exploitation and abuse at scales never seen before. And in the postmodern mind, the latter was the result of the former.

Thus, many people today—especially those in secular Western cultures who’ve implicitly embraced the postmodern ethos—prefer orthopraxy over orthodoxy. That is, they care more about right practice than right belief.

What good is right belief, after all, if it doesn’t lead to good ethical practice?

What good is talking the talk if one doesn’t also walk the walk?

The way I explained it recently to a friend, who is a very influential writer in my denomination, is that people today don’t really ask the question, “Is this idea propositionally correct?” They instead ask the question, “Does it work?”

In other words, they’re less interested in the correctness of abstract ideas—especially when it comes to religion and spirituality—and more interested in whether those concepts lead to and are reflected in lives of love and kindness. If that ethical fruit doesn’t show up in the life of the one promoting the particular idea, they have no interest in those ideas.

Thus, in this context, to be someone who promotes “truth” is to be someone who not only promotes ideas but demonstrates that those ideas show up in a life of consistency and integrity.

So the “truth about marriage” isn’t simply talking about the correct arrangement of marriage in the abstract; it’s actually living out a consistent—though admittedly imperfect—marriage in the practical.

The “truth about the Sabbath” isn’t simply trying to prove that Saturday is the Sabbath; it’s entering into the joy and rest of Sabbath in the practical, and reflecting a “Sabbathy” (i.e., restful) disposition every day of the week.

Epistemology

Epistemology, as I’ve shared before, is the study of the nature and scope of knowledge, and how we come to know what we know.

In this case, understanding that “truth,” according to the biblical writers, is more contextual and story-based—rather than absolute, timeless, and binary—naturally leads to greater epistemic humility.

That is, it leads us to be more open-handed about our convictions, recognizing that “truth” is a lot more nuanced and complex than us Western thinkers have recognized.

To point to the map analogy again from last week: recognizing that every map has its limits and purpose, and isn’t designed to be an exhaustive representation of any terrain, I can temper my claims about the scope and extent of its claims—and also my grasp of them (which thus affects my willingness to act with certainty about those claims).

So, too, with truth—which again leads to a certain level of humility.

This doesn’t mean truth is completely relative—as though we could never make bigger claims that move beyond our specific context—nor that we can’t have a high degree of confidence in what we believe or maintain is true.

It just means that we hold—and present—our convictions with grace, acknowledging the ad hoc and contextual nature of truth.

Evangelism

For a number of reasons, I don’t really like the word “evangelism” that much these days—mostly because of some negative baggage in my mind—preferring the phrase “missional living” (or something like that). But I wanted to keep the alliteration going, so I chose it.

And the point is this: understanding that “truth” isn’t correct propositional ideas, but is reliability and faithfulness, has huge implications for the way we approach evangelism and mission. Huge.

I won’t sugarcoat it: in my opinion, my faith community has historically had an unhealthy obsession with trying to convince people to accept correct propositional ideas. That’s largely been our singular goal with evangelism—with the ethical fruit, mentioned above, almost an afterthought.

But recognizing the holistic and embodied nature of truth totally calls this approach into question, reframing both the methods and goals of evangelism.

The method is no longer the act of propositional argumentation, hoping to convince people of the correctness of our abstract ideas.

And the goal is no longer trying to get people to mentally assent to the correctness of our abstract ideas.

Instead, the method is a holistic and integrative approach where we embody truth as much as we share propositional ideas. And when we do share a specific message, we don’t present it as a list of abstract ideas, but place it within the framework of a larger, embodied narrative.

At the same time, the goal of evangelism is to draw people into lives of love—in all its many dimensions. This means we want them to become whole people in all areas of life—emotionally, relationally, socially, physically, spiritually, intellectually.

To be sure, rational assent is a part of that—but only insofar as it’s placed within the context and serving the goal of helping others become people of love.

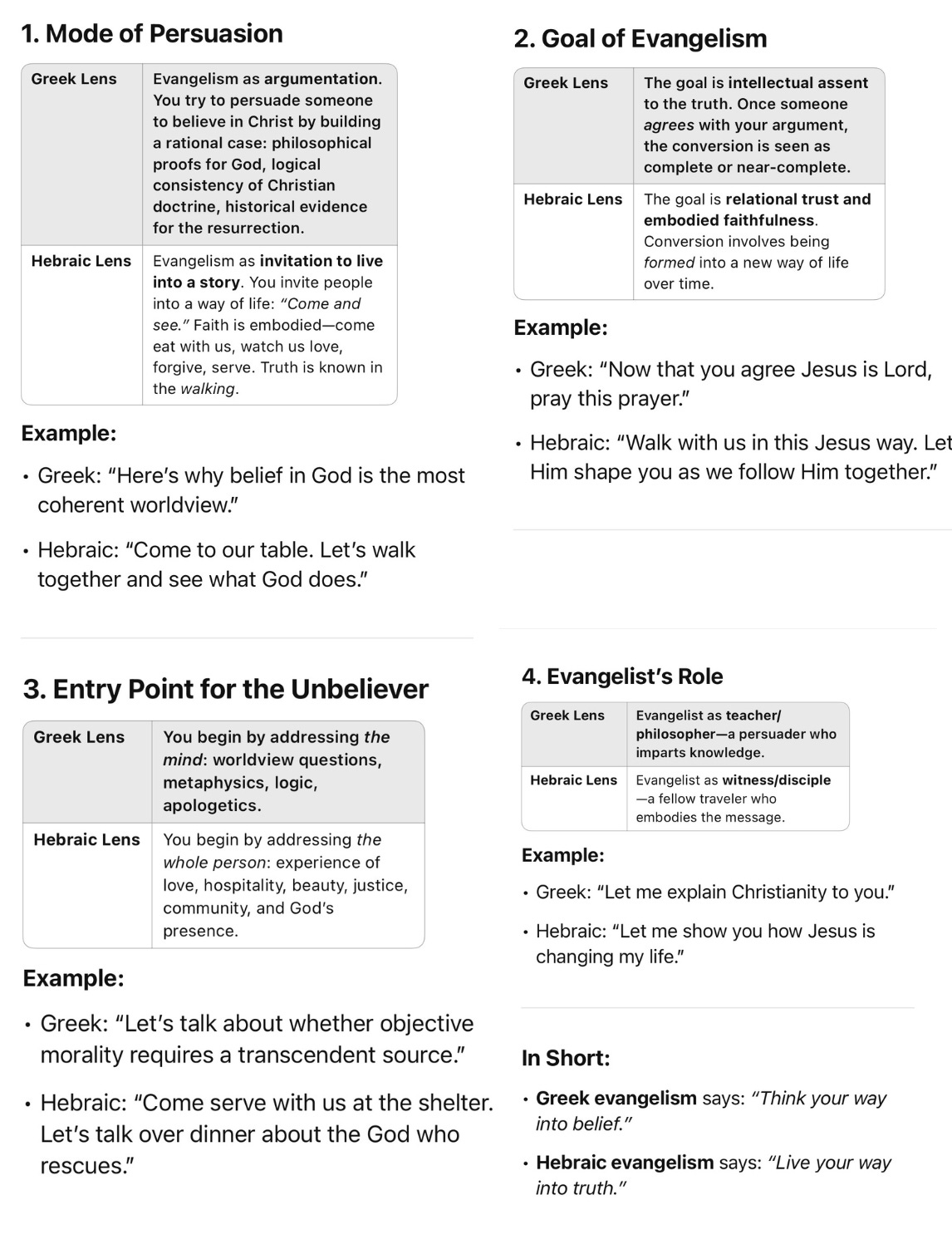

I could say a lot more about this particular point (since it’s so important to me). But instead, I thought I’d just show a chart below, created by ChatGPT, that illustrates the differences between Greek-influenced evangelism, which primarily focuses on propositional correctness, and Hebrew-influenced evangelism, which takes a much more holistic, all-of-life approach.

It’s absolutely dynamite!

Getting practical

So let me return to the first scenario above and show you how all this plays out on a practical level.

Your neighbor’s husband dies and that’s devastating to you. You care deeply about her and don’t want her to stay in a perpetual funk. You also want to share “truth” with her, and the truth in that moment is reminding her of her belovedness and embodying it toward her.

Your ultimate goal with her is not that she’d accept some propositional theological ideas but that she’d experience and be formed into a person of hope and love.

So you bake her cookies, invite her over for dinner, cry with her. You do this consistently and repeatedly, as it’s helpful to her.

And in those moments, you never feel the need to correct her faulty “theology,” because being a truth-teller to her in that moment comes through living a resurrection life—full of hope, comfort, and encouragement. By living such a life—however imperfectly—you’re embodying what happens after a person dies.

Eventually, over time, she asks you about your understanding of God and spirituality. Slowly, bit-by-bit, over many conversations—sometimes while on a walk together, other times while serving refugees together—you share your understanding of God’s story with her—about how God is ultimately working toward the renewal of all things, and how Jesus will some day return, call the dead back to life, and live in eternal fellowship with all those who’ve embraced and embodied his love.

She just smiles and nods—but doesn’t mentally assent to what you’ve shared.

But three months later, you have opportunity to organically revisit the same story. And five months after that she wakes up one day and embraces that story—mostly because you, as the story-teller, have demonstrated that the story has been reflected in a life of faithfulness, integrity, and kindness.

Or maybe she never does explicitly step into that story—but she feels your love, and your convictions certainly keep her perpetually curious.

And that’s all OK—because this is what it means to be a person of truth.

Shawn is a pastor and church planter in Portland, Maine, whose life, ministry, and writing focus on incarnational and embodied expressions of faith. The author of four books and a columnist for Adventist Review, he is also a DPhil (PhD) candidate at the University of Oxford, focusing on nineteenth-century American Christianity. You can follow him on Instagram, and listen to his podcast Mission Lab.