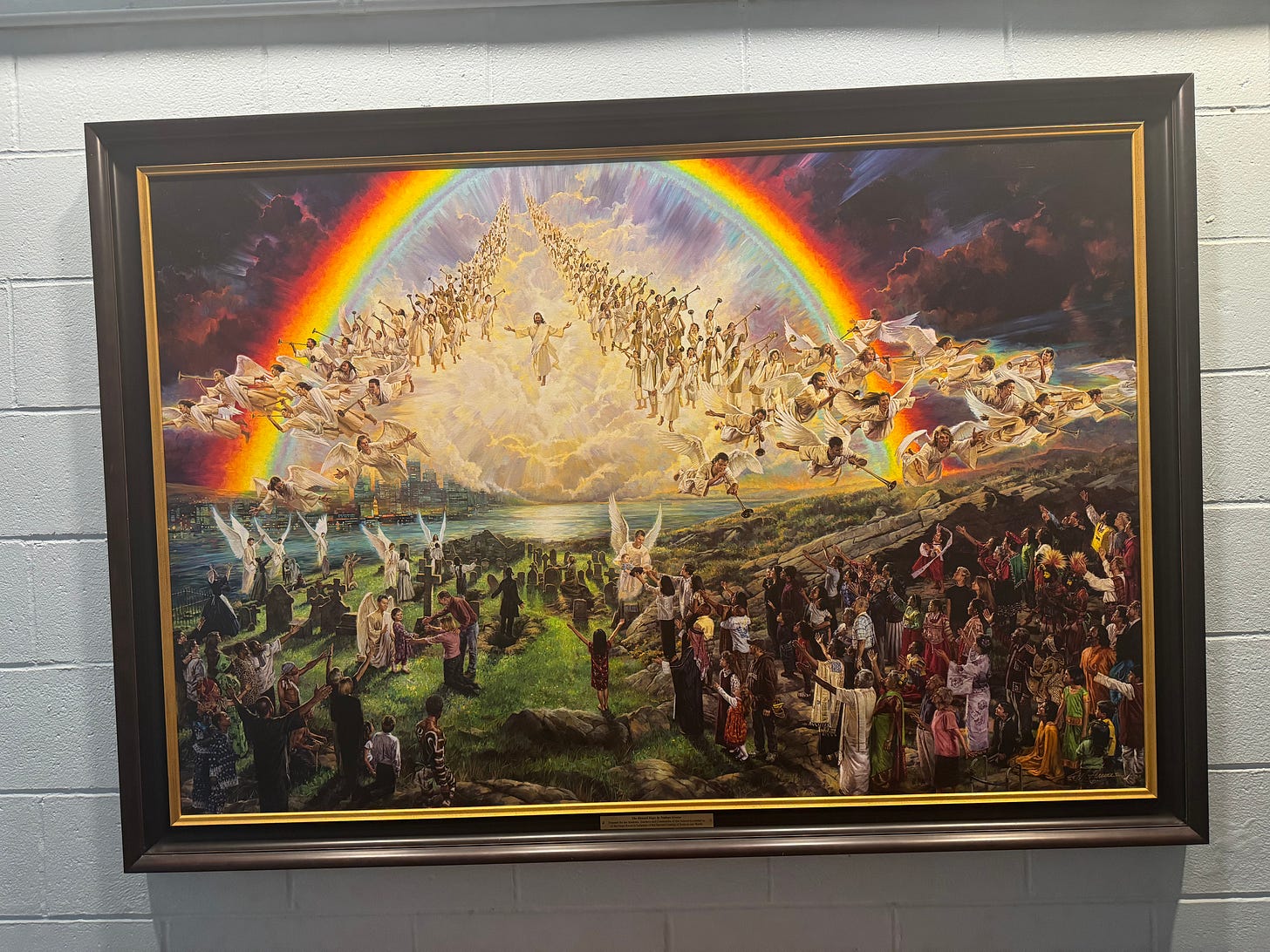

(Photo credit: me—of a painting by Adventist artist, Nathan Greene, called “The Blessed Hope,” which hangs in the hallway of my kids’—and wife’s—school, Pine Tree Academy)

(An eight-minute read.)

Soon after the re-election of Donald Trump, I was talking to a good friend who isn’t a Christian and is super progressive. She was, not surprisingly, absolutely devastated and extremely confused.

What she couldn’t understand was how it was possible for America to have chosen to go backward instead of continuing to move forward toward progress. In electing Trump, she lamented, we were choosing regressive views on race, gender, sexuality, immigration, the environment, economics.

It was extremely disorienting mostly because the assumption among progressives is that progress is inevitable. Ever since the Enlightenment, many in the West have believed that, through our collective reasoning, the world is moving toward a utopian future.

Granted, it may take a while, but we’ll eventually get there.

Simultaneous to this Enlightened progressivism, many Christians in the West have also seen a theological basis for this optimism, believing in what has been referred to as “postmillennialism.”

Based on a particular interpretation of the New Testament’s book of Revelation, postmillennialism proposes that Christ will return after the world experiences a thousand years of peace, prosperity, and righteousness.

Again, progress is the world’s inevitible future.

This postmillennialism is perhaps epitomized most poignantly by what’s often called the “Social Gospel,” which came of age at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. Early proponents of the Social Gospel believed it was their task to actively promote and achieve the social welfare of all, especially the impoverished and marginalized, and in so doing, help usher in Christ’s millennial kingdom.

As Washington Gladden, one of the most notable exponents of the Social Gospel, proclaimed in 1909:

What the prophet [Isaiah] beholds in his vision is the kingdom of God, the reign of righteousness and truth and love in the earth. . . . It is all coming true. It is no longer a dream, it is proving to be a reality. The city of God, the new Jerusalem, which the Revelator saw coming down from heaven, is beginning to materialize before our eyes.

But postmillennialists, soon after Gladden declared this, experienced a rude awakening—which many other secular progressives and Christian postmillennialists have historically faced: five years after Gladden’s declaration, all of Europe—the epicenter of enlightened thinking and civilization—erupted into a “world” war.

As historian Jon R. Stone explains, “The guns of August 1914, which unleashed four years of catastrophic horror unimaginable except in ‘apocalyptic’ terms, effectively shattered the hopes of the Social Gospelers” as well as other postmillennialists.

And this is why Enlightened progressivism and Christian postmillennialism have waxed and waned throughout their history: just when adherents start dreaming about attaining millennial or progressive glory, something catastrophic—instigated by supposedly-enlightened humans—happens, calling into question the inevitability of human progress.

Whether it was Europe’s Thirty Years’ War or the French Revolution or the American Civil War or World War I or the Holocaust or, yes, the re-election of Donald Trump, our inevitable march toward progressive utopianism doesn’t seem to be a sure bet.

And in the wake of such events, when we’re trying to sort through the rubble of our disillusionments, what is left?

My proposal: premillennialism and the return of Jesus.

“Then the end shall come”

I don’t mean to be flippant about this sort of disillusionment or attempt to score theological points. Nor do I wish to make a statement about whether I think Trump’s re-election is progress or regress (though I suspect the informed reader could hazard a guess).

But in response to my friend’s disillusionment, which I did my best to empathize with, I also took the opportunity to briefly explain how I saw things.

The way I see it, progress isn’t inevitable because I believe in premillennialism.

To be clear: I have plenty of questions—mostly from a historical and sociological perspective—about premillennialism, believing that adherence to it can lead to all sorts of unfortunate and ugly consequences.

It can foment great fear, conspiratorial thinking, escapism, and exclusivism—and, sadly, it can also shape American policy in ways that seem to contradict the principles of God’s kingdom of love (as expressed, for example, in America’s unconditional support for the actions of modern Israel).

It can also provide us with hope, of course.

Simply put, premillennialism is the belief that Jesus will return prior to a thousand-year, millennial reign. It assumes that the only way the world will get better, and experience true “utopia,” is the return of Christ—when he will set the world fully aright at last.

As such, moral, environmental, and social decline are inevitable. Things will get worse before they get better—and will only get better when God’s kingdom is fully realized through Christ’s cleansing work upon his return (though on this, please read this).

There are many different versions of premillennialism, but what they all have in common is the belief, based on a reading of Scripture and an observation of the world, that Jesus will return not as a response to humanity’s ultimate progress but as its true and only source.

Historically, premillennialism had antecedents in seventeenth-century Europe, but really found its legs in nineteenth-century American Christianity. Beginning in the early nineteenth century and resulting from the convergence of many historical and theological factors (not least of which was the bloody and violent French Revolution), various new Christian movements in America started banging the premillennial drum.

Social and political chaos, after all, inevitably causes people to reexamine their assumptions about where they think the world is headed (which is a reality at play today as well).

Though Joseph Smith and his Mormon followers were prominent premillennialists, the most famous premillennialists of the nineteenth century were William Miller and his Millerites. By 1844, the year they believed Christ would return, the Millerites numbered upwards of 100,000 people—mostly hailing from New England and other northeastern states.

After the “Great Disappointment” of October 22, Miller’s followers eventually splintered into various Adventist groups—including the Seventh-day Adventists (my faith community), which is now the largest of all Adventist denominations, numbering some 23 million adherents worldwide.

Other denominations, like the Jehovah’s Witnesses, followed in Miller’s premillennialist wake—but eventually, by the turn of the twentieth century, premillennialism migrated into more mainstream Protestant denominations, being adopted by the vast majority of conservative, “Bible-believing” Christians.

It became one of the points of contention between the conservative “fundamentalists” and the progressive “modernists” during the so-called fundamentalist-modernist controversy in the early twentieth century, with fundamentalists—who eventually adopted the name “evangelical” by the middle of the twentieth century as a way to purge themselves of the negative associations of fundamentalism—largely affirming premillennialism (and the modernists affirming, among other things, the aforementioned Social Gospel).

The more popular versions of premillennialism, subscribed to by evangelicals today, typically promote some sort of Dispensationalist framework, which was first introduced by British theologian John Nelson Darby in the nineteenth century (and disseminated widely in America through the publication of the very popular Scofield Reference Bible).

Among other things, Dispensationalists believe that Christ will someday soon secretly remove his believers from the earth, bringing them to heaven, at which point there will be seven years of massive tribulation and societal upheaval. This will be accompanied by the restoration of literal Israel, with God fulfilling his biblical promises to the nation, who will also be persecuted by the Antichrist. Eventually, however, God will return in glory and rescue Israel and set up his millennial kingdom.

As I said, there are many different versions of premillennialism, and they often go to some rather dark, depressing, and fear-inducing places.

But for my part, I continue to affirm premillennialism—admittedly, partly because the state of the world, but also, candidly, because I have a hard time seeing how the story of Scripture points in any other direction.

Simply put, I do believe that the story of Scripture promotes the idea of premillennialism and the soon return of Jesus.

But I don’t affirm a premillennialism that sees a Jesuit behind every bush or a premillennialism that encourages an escapist mentality (maintaining that “God is just going to burn it all up anyway”).

And I certainly don’t promote a Dispensationalist premillennialism which, among other things, declares an unconditional allegiance to everything the state of Israel decides to do.

I affirm a hopeful premillennialism, believing that, try as we might to fix the world ourselves, we need intervention from without in order to restore the world to the love and peace for which it was created.

I also affirm an activist premillennialism, maintaining that, the inevitable incompleteness of our task notwithstanding, we’re still called to embody God’s kingdom of love, serving, at the very least, as “sign posts” to what will only be fully realized when Christ at last returns (it was a belief in the soon return of Jesus that, perhaps counterintuitively, partially propelled Adventist anti-slavery activism).

At the same time, I affirm premillennialism because—quite frankly—I long to see the face of Jesus and experience the Beatific Vision, which will be the fulfillment of my heart’s deepest longings and desires.

I believe I was created to be in God’s literal presence, which will lead to the most intense, overwhelming, and happy feelings I could ever experience.

So why would I not be a premillennialist?

Why would I not want that to happen soon?

To be sure, I definitely don’t know if this will happen tomorrow, next week, or a hundred years from now—and I’m not into fortune telling or “signs of the times” hysteria.

Neither do I allow my faith to ebb and flow based on the degree to which some new “sign” ramps up my excitement.

Nor will I run around, like a man with his hair on fire, warning everyone that the end is near and that they’d better get ready.

But with William Miller, after he experienced his final failed prediction about Christ’s return, I say:

Although I have been twice disappointed, I am not yet cast down or discouraged. . . . I have fixed my mind upon another time, and here I mean to stand until God gives me more light.—And that is Today, TODAY, and TODAY, until he comes, and I see Him for whom my soul yearns.

And with John the Revelator, in the New Testament’s second-to-last verse, I say, “Even so, come, Lord Jesus.”

Shawn is a pastor and church planter in Portland, Maine, whose life, ministry, and writing focus on incarnational and embodied expressions of faith. The author of four books and a columnist for Adventist Review, he is also a DPhil (PhD) candidate at the University of Oxford, focusing on nineteenth-century American Christianity. You can follow him on Instagram, and listen to his podcast Mission Lab.

dispensationalist pre. also claims that 144,000 converted Jews will finish the gospel commission during the 7-yr trib. this is the best way to cut the nerve of Christian mission that I can imagine.

Wonderful thoughts on premillennialism. I share much of the same view. As a hopeful premillennialism, I've found Richard Mouw's book "When the king's come marching in" extremely helpful in that exercise of hope. He makes nice connections in the book of Isaiah to propose that our cultural production will some how face continuity in the New Jerusalem. So, even though we believe that the world is coming to an end, the fruits of our hands are seeds for eternity even though they may face an interruption here.