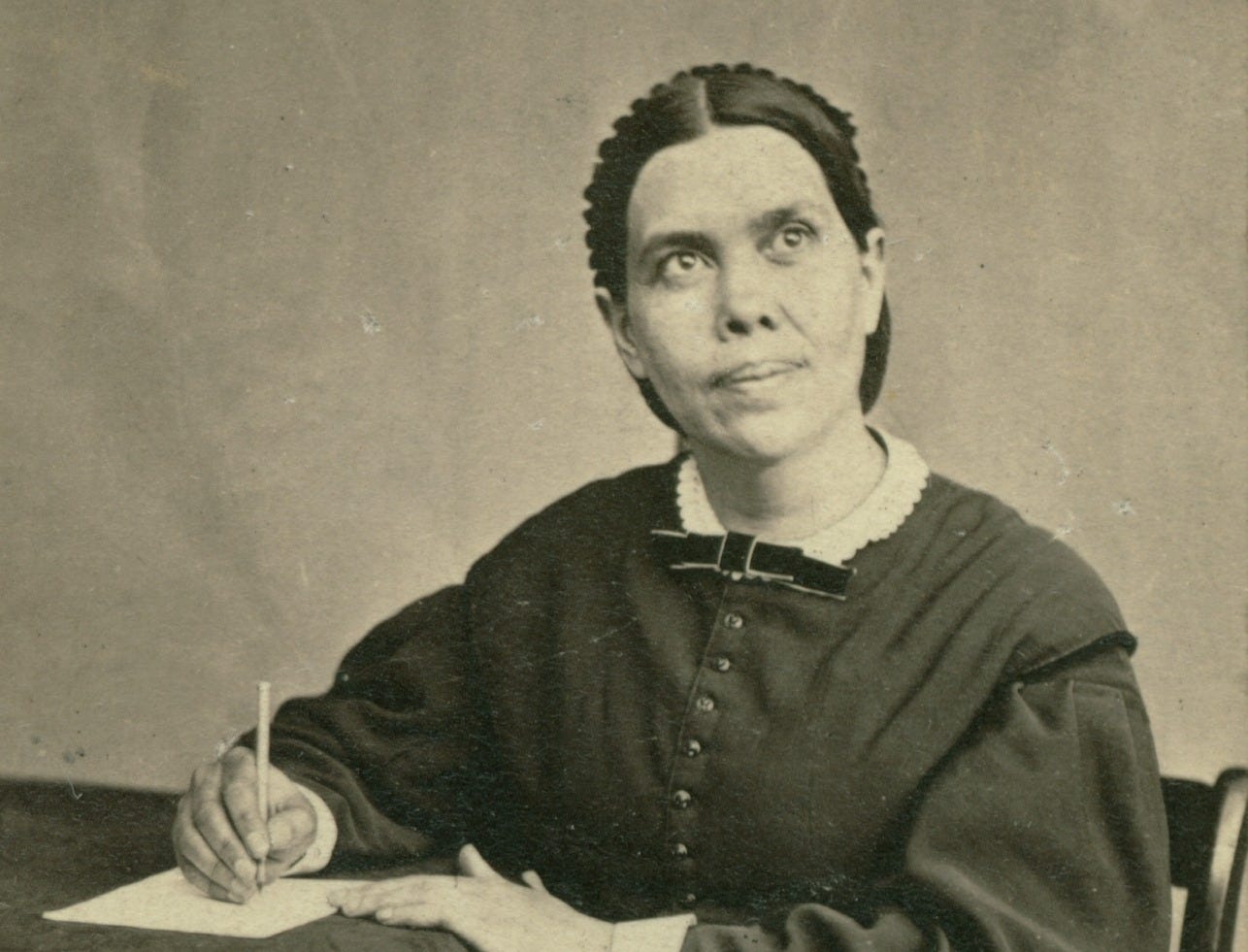

Courtesy of the Ellen G. White Estate, Inc.

(A seven-minute read.)

The other day, I picked up a book by Ellen White, one of my denomination’s co-founders, and was suddenly reminded of something as I read: I think it’s safe to say that there hasn’t been a bigger influence on my theological thinking than her.

This may come as a troubling surprise to people for various reasons.

For Christians outside of Seventh-day Adventism, it may seem troubling because of the implication that I’m apparently allowing an extra-biblical source to have too much sway on my thinking.

But such a charge rings a bit allow, I’d humbly submit, when there are Christians in the world who refer to themselves as “Calvinists” or “Lutherans” or “Wesleyans.”

Though I’m speaking of her as a major influence on my theological thinking, I don’t call myself a “Whitean.”

And I’m not making the claim—at least here—that, unlike the fountainheads of the various systems above, she is influential on my theological thinking because of some quasi-biblical authority I ascribe to her.

I’m referring to her, at least in these reflections, simply as a theologian—not as a “prophet” (as most Adventists would likely refer to her, which is a discussion I’ll leave for another time).

There may still be others, hailing largely from within my Adventist faith community, who are equally troubled by this reality—mostly because of how strict, rigid, and legalistic she has been made out to be theologically.

Therefore, anyone who claims to be significantly shaped by her should be given a wide berth.

And to this, I say: I get it. I totally get it.

This has, admittedly, been a huge, huge problem.

And, honestly, with something like 100,000 pages of her written material published—in addition to compilations that have been stitched together by publishers after her death—it feels like there’s a lot of opportunity to use her writings as a proverbial club with which to beat people over the head.

She could also, admittedly, be very dogmatic at times—probably more dogmatic than most twenty-first-century thinkers would be comfortable with.

But, in her defense, that was very much par for the course for her nineteenth-century context (as N. T. Wright has quipped: the nineteenth century had many problems, but a low self-esteem wasn’t one of them).

But, here, I’m not necessarily talking about Ellen White as a person who tells people what to do (though a discussion about that at some point would be appropriate).

I’m, again, talking about Ellen White as a theologian—someone who offers reflections on the nature, character, and actions of God.

And to that end, I’d submit that, as a theologian, she offered very unique insights—and, even more significantly, perhaps introduced the most love-centered theology I’ve ever encountered.

Take, for example, some of the opening paragraphs of the book I picked up, Patriarchs and Prophets—which is the first book in a five-book series often referred to as the Conflict of the Ages series. Granted, it’s not a “systematic theology,” like many theologians would insist a person must write in order to be considered a “bona fide” theologian. Instead, it’s a narrative exposition, based on the Bible, of the universe’s history—from before time began, to its ultimate consummation in the “ceaseless ages of eternity.”

Notice the very first sentences of this book, in a chapter entitled “Why Was Sin Permitted?”

“God is love.” 1 John 4:16. His nature, His law, is love. It ever has been; it ever will be.

Similarly, in the next paragraph, she continues:

Every manifestation of creative power is an expression of infinite love. The sovereignty of God involves fullness of blessing to all created beings.

Then, two paragraphs later:

The history of the great conflict between good and evil, from the time it first began in heaven to the final overthrow of rebellion and the total eradication of sin, is also a demonstration of God’s unchanging love.

Again, on the next page:

The law of love being the foundation of the government of God, the happiness of all intelligent beings depends upon their perfect accord with its great principals of righteousness. God desires from all His creatures the service of love—service that springs from an appreciation of His character. He takes no pleasure in a forced obedience; and to all He grants freedom of will, that may render Him voluntary service.

And on and on it goes.

Her Conflict series continuously develops these themes, placing all her theological reflections within the context of God’s character of self-emptying, self-sacrificing love.

Elsewhere in the series, in her book The Desire of Ages—which is an exposition on the life of Christ—she shares what I think is one of the most profound and unique statements ever written. Speaking of the consequences of humanity’s initial fall, she explains:

The earth was dark through misapprehension of God. That the gloomy shadows might be lightened, that the world might be brought back to God, Satan’s deceptive power was to be broken. This could not be done by force. The exercise of force is contrary to the principles of God's government; He desires only the service of love; and love cannot be commanded; it cannot be won by force or authority. Only by love is love awakened.

And thus sets the scene for the unfolding of the whole cosmic narrative she develops.

As I said, such an idea—that God’s character of love is the center of his divine reality and actions, and is also the subject of the universe’s ultimate deliberations—is the thread that unites all her theological reflections.

And I highlight this particular point for two reasons:

First, as I shared at the beginning, I owe my love-centered theology chiefly and primarily to her. Though I don’t call myself a “Whitean,” my theology is basically an outworking of a “Whitean” theological framework.

Again, there are probably plenty of people from my faith community for whom this sounds scary. And I understand that.

But it’s actually a very good thing, I’d submit—that is, if one accepts the idea that the center of “Whitean” theology is God’s love.

If one leaves aside, for a moment, the personal “testimonies” she wrote to individual people—which have then been used by thousands of people ever since as the main source of their “Whitean” diet—and sticks to her major theological reflections in the Conflict series (and similar works like Steps to Christ, Thoughts From the Mount of Blessing, and Christ’s Object Lessons), which focus on the nature and character of God, and the person of Christ, I think it would be hard to get around the idea that the love of God was the main focus of her theological vision.

Indeed, we get a clue about this with the first three and the last three words of her Conflict series.

What are they? As many others have pointed out, simply this: “God is love.”

And thus, to whatever degree you may appreciate my emphasis on God’s love, you can largely thank Ellen White.

Second, I raise this point because, in many regards, her love-centered theological framework was unique and—I might be tempted to say—revolutionary.

Admittedly, I certainly haven’t examined every crack and crevice and corner of Christian theology prior to her rise in the nineteenth century. But from what I’ve encountered, I don’t see many parallels to her theological vision.

For one, much of Christian theology—at least in Protestant circles—prior to Ellen White was largely influenced by Reformed and Calvinist thinking, which gave primary emphasis to ideas like predestination, God’s sovereign and irresistible will, and humanity’s inability.

Beginning in the eighteenth century, through the efforts of people like John Wesley, there was, of course, a growing number of Christians who began to loosen their commitment to and even outright reject the Calvinistic paradigm that had held sway for a couple hundred years. And this became especially pronounced among American thinkers in the nineteenth century.

Ellen White followed in this vain, of course. She wasn’t a Calvinist and, in many ways, worked out a theological framework that owed a great deal to John Wesley (as my former seminary professor, Denis Fortin, and my former undergraduate professor, Woodrow Whidden, so wonderfully impressed upon me during my time under their tutelage).

But what arguably separated her from these other non-Calvinist thinkers, including Wesley, was her continuous and repeated focus on God’s character of love, especially within the framework of a larger “cosmic conflict”—the latter of which is arguably an echo, in some regards, of the third-century Origen of Alexandria and the seventeenth-century Puritan writer, John Milton.

Again, there were others who started developing an emphasis on God’s character of love to greater degrees in the nineteenth century (I’m thinking especially of someone like the Unitarian theologian/preacher William Ellery Channing), but none of them placed that within the context of a larger “cosmic conflict” wherein a focus on God’s character is the main issue at play.

In some ways, then, Ellen White borrowed from the soteriology of Wesley, the love-centered ethics of Channing, and the theodicy of Origen and Milton.

And she combined them all to create her own unique theological paradigm.

And I’m so down with it.

Shawn is a pastor in Portland, Maine, whose life, ministry, and writing focus on incarnational expressions of faith. The author of four books and a columnist for Adventist Review, he is also a DPhil (PhD) candidate at the University of Oxford, focusing on nineteenth-century American Christianity. You can follow him on Instagram, and listen to his podcast Mission Lab.

So very blessed by your writing and in agreement!

I appreciate your reflections on Ellen White and largely agree. My sticking point is her "The Great Controversy"

Although the final three words are "God is love", I struggle to see much love demonstrated in her strident anti- Catholicism. Yes, she was a child of her times, but our faith community still leads with this book in massive random mailings and Facebook teaching by the esteemed General Conference President of said faith group. I wish I could get over this hurdle, but so far I trip on it repeatedly.

Thanks for your emails. I find them uplifting and stimulating.

Richard Myers